WHAT IS TAKAYASU’S ARTERITIS?

Takayasu’s arteritis is an unusual type of vasculitis, a group of disorders that causes blood vessel inflammation. In Takayasu’s arteritis, the inflammation damages the big artery that carries blood from your heart to the rest of your body (aorta) and its main branches.

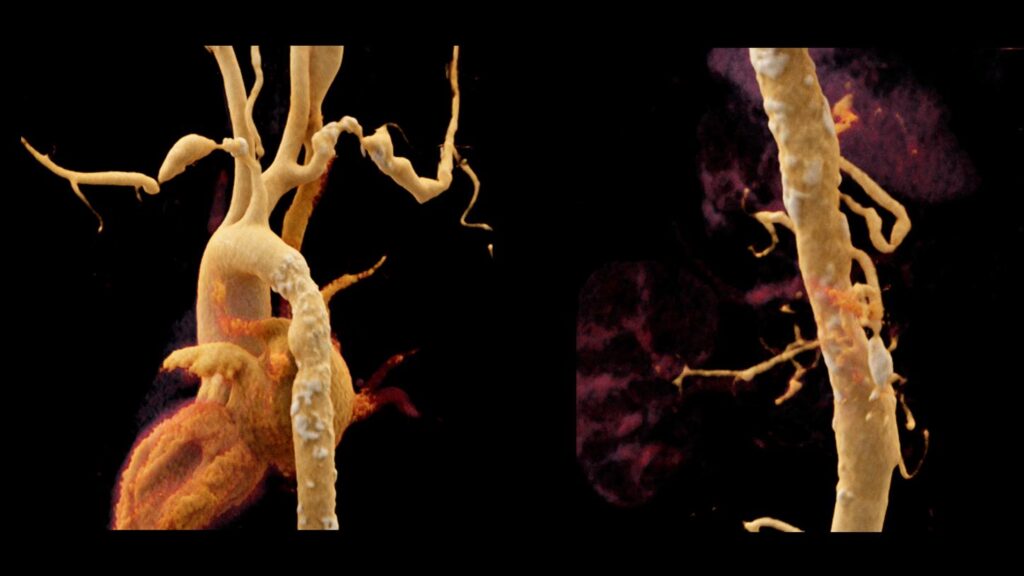

The disease could lead to narrowed or blocked arteries, or to weakened artery walls that might bulge (aneurysm) and tear. It could also lead to arm or chest pain, high blood pressure, and ultimately heart failure or stroke.

If you do not have symptoms, you might not require treatment. But most people with the disease require medications to control inflammation in the arteries and to prevent complications. Even with treatment, relapses are common, and your symptoms might come and go.

TAKAYASU’S ARTERITIS SYMPTOMS

The signs and symptoms of Takayasu’s arteritis usually happen in two stages.

Stage 1

In the first stage, you are likely to feel unwell with:

- Fatigue

- Unintended weight loss

- Muscle and joint aches and pains

- Mild fever, sometimes followed by night sweats

Not everyone has these precocious signs and symptoms. It is possible for inflammation to damage arteries for years before you realize something is wrong.

Stage 2

During the second stage, inflammation causes arteries to contract so less blood and oxygen and fewer nutrients reach your organs and tissues. Stage two signs and symptoms might include:

- Weakness or pain in your limbs with the use

- A weak pulse, trouble getting blood pressure, or a difference in blood pressure between your arms

- Light-headedness, dizziness, or fainting

- Headaches or visual changes

- Memory issues or trouble thinking

- Chest pain or shortness of breath

- High blood pressure

- Diarrhea or blood in your stool

- Too few red blood cells (anemia)

WHEN SHOULD YOU SEE A DOCTOR?

Look for immediate medical attention for shortness of breath, chest or arm pain, or signs of a stroke, like a face drooping, arm weakness, or having trouble speaking.

Make an appointment with your doctor or primary care physician if you have other signs or symptoms that worry you. Early detection of Takayasu’s arteritis is crucial for effective treatment.

If you have already been diagnosed with Takayasu’s arteritis, keep in mind that your symptoms might come and go even with effective treatment. Pay attention to symptoms similar to those that happened originally or to any new ones, and be sure to tell your doctor or primary care physician immediately about changes.

TAKAYASU’S ARTERITIS CAUSES

With Takayasu’s arteritis, the aorta and other important arteries, including those leading to your head and kidneys, could become inflamed. Over time the inflammation causes changes in these arteries, including thickening, contraction, and scarring.

Nobody knows exactly what causes the initial inflammation in Takayasu’s arteritis. The condition is likely an autoimmune disorder in which your immune system attacks your own arteries by mistake. The disease might be triggered by a virus or other infection.

TAKAYASU’S ARTERITIS RISK FACTORS

Takayasu’s arteritis mainly affects girls and women younger than 40 years. The disorder happens worldwide, but it is most common in Asia. Sometimes the state runs in families. Researchers have identified specific genes related to Takayasu’s arteritis.

TAKAYASU’S ARTERITIS COMPLICATIONS

With Takayasu’s arteritis, cycles of inflammation and healing in the arteries may lead to one or more of the following complications:

- Hardening and narrowing of blood vessels, which could cause decreased blood flow to organs and tissues.

- High blood pressure, generally a result of decreased blood flow to your kidneys.Inflammation of the heart, which might affect the heart muscle or the heart valves.

- Heart failure because of high blood pressure, inflammation of the heart, and aortic valve that enables blood to leak back into your heart, or a combination of these.

- Stroke, which happens as a result of decreased or blocked blood flow in arteries leading to your brain.

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA), which is also known as a mini-stroke. Transient ischemic attack (TIA) serves as a warning sign because it produces symptoms similar to a stroke but does not cause permanent damage.

- Aneurysm in the aorta, which happens when the walls of the blood vessel weaken and stretch, forming a bulge that has the potential to break.

- Heart attack, which might happen as a result of decreased blood flow to the heart.

PREGNANCY

A healthy pregnancy is possible in women who have Takayasu’s arteritis. But the disease and drugs used to treat it could affect your fertility and pregnancy. If you have Takayasu’s arteritis and are planning on becoming pregnant, work with your doctor or primary care physician to develop a plan to limit complications of pregnancy before you conceive. See your doctor or primary care physician regularly during your pregnancy for check-ups.

TAKAYASU’S ARTERITIS DIAGNOSIS

Your doctor or primary care physician will ask you about your signs and symptoms, perform a physical examination, and take your medical history. He or she might also have you undergo some of the following tests and procedures to help rule out other conditions that resemble Takayasu’s arteritis and to confirm the diagnosis. Some of these tests might also be used to check on your progress during treatment.

Blood tests – These tests could be used to look for signs of inflammation. Your doctor or primary care physician might also check for anemia.

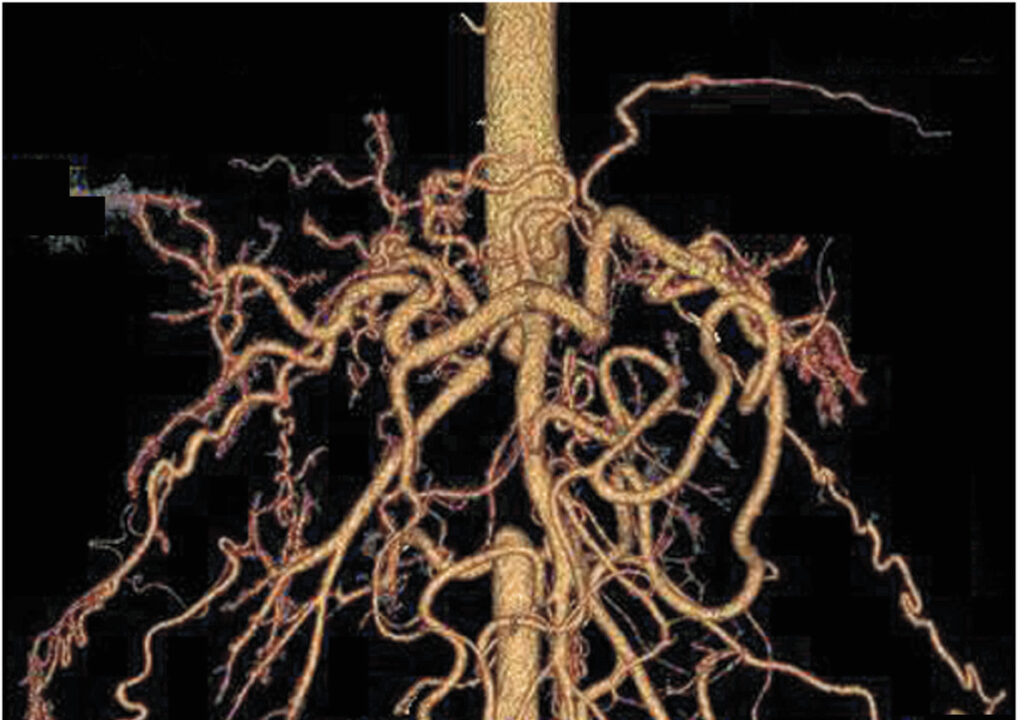

X-rays of your blood vessels (angiography) – During an angiogram, a long, flexible tube (catheter) is inserted into a big artery or vein. A special contrast dye is then administered into the catheter, and X-rays are taken as the dye fills your arteries or veins.

The resulting pictures allow your doctor or primary care physician to see if blood is flowing normally or if it is being slowed or interrupted due to narrowing (stenosis) of a blood vessel. A person with Takayasu’s arteritis usually has several regions of stenosis.

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) – This less invasive form of angiography produces detailed pictures of your blood vessels without the use of catheters or X-rays. Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) works by using radio waves in a strong magnetic field to produce data that a computer turns into detailed pictures of tissue slices. During this test, a contrast dye is administered into a vein or artery to help your doctor or primary care physician better see and examine the blood vessels.

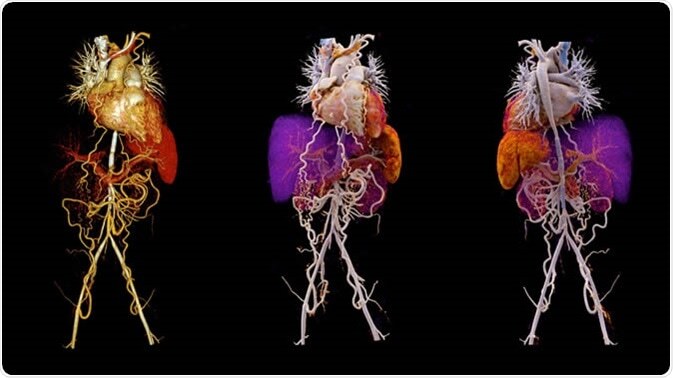

Computerized tomography (CT) angiography – This is another non-invasive form of angiography combining computerized analysis of X-ray pictures with the use of intravenous contrast dye to allow your doctor or primary care physician to check the structure of your aorta and its nearby branches and to monitor blood flow.

Ultrasonography – Doppler ultrasound, a more sophisticated version of the common ultrasound, has the ability to produce very high-resolution pictures of the walls of specific arteries, like those in the neck and shoulder. It might be able to detect subtle changes in these arteries before other imaging techniques could.

Positron emission tomography (PET) – This imaging test is usually done in combination with computerized tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Positron emission tomography (PET) could measure the intensity of inflammation in blood vessels. Before the scan, a radioactive drug is administered into a vein or an artery to make it easier for your doctor or primary care physician to see areas of reduced blood flow.

TAKAYASU’S ARTERITIS TREATMENT

Treatment of Takayasu’s arteritis concentrates on controlling inflammation with medications and preventing further damage to your blood vessels.

Takayasu’s arteritis could be difficult to treat because the disease might remain active even if your symptoms improve. It is also possible that irreversible damage has already happened by the time you are diagnosed.

On the other hand, if you do not have signs and symptoms of severe complications, you might not need treatment or you might be able to taper and stop treatment if your doctor or primary care physician recommends it.

MEDICATIONS

Talk with your doctor or primary care physician about the drug or drug combinations that are options for you and their possible side effects. Your doctor or primary care physician might prescribe:

- Corticosteroids to control inflammation – The first line of treatment is generally a corticosteroid, like prednisone (Prednisone Intensol, Rayos). Even if you start feeling better, you might require to continue taking the drug long-term. After a few months, your doctor or primary care physician might slowly start to lower the dose until you reach the lowest dose you require to control inflammation. Ultimately your doctor or primary care physician might tell you to stop taking the medication completely.

Possible side effects of corticosteroids include weight gain, increased risk of infection, and bone weakening. To help prevent bone loss, your doctor or primary care physician might recommend a calcium supplement and vitamin D.

- Other drugs that suppress the immune system – If your condition does not respond well to corticosteroids or you have trouble as your medication dose is lowered, your doctor or primary care physician might prescribe drugs like methotrexate (Trexall, Xatmep, others), azathioprine (Azasan, Imuran) and leflunomide (Arava). Some people respond well to medications that were developed for people receiving organ transplants, like mycophenolate mofetil (CellCept). The most frequent side effect is an increased risk of infection.

- Medications to regulate the immune system – If you do not respond to standard treatments, your doctor or primary care physician might recommend drugs that correct abnormalities in the immune system (biologics), although more research is required. Instances of biologics include etanercept (Enbrel), infliximab (Remicade), and tocilizumab (Actemra). The most frequent side effect of these drugs is an increased risk of infection.

SURGERY

If your arteries become severely narrowed or blocked, you might require surgery to open or bypass these arteries to allow an uninterrupted flow of blood. Usually, this helps to improve specific symptoms, like high blood pressure and chest pain. In some cases, though, the narrowing or blockage might occur again, needing a second procedure.

Also, if you develop large aneurysms, surgery might be required to prevent them from rupturing.

Surgical options are best performed when inflammation of the arteries has been decreased. They include:

Bypass surgery – In this procedure, an artery or a vein is removed from a different section of your body and attached to the blocked artery, providing a bypass for blood to flow through. Bypass surgery is generally performed when the narrowing of the arteries is irreversible or when there is a significant obstruction to blood flow.

Blood vessel widening (percutaneous angioplasty) – This procedure might be indicated if the arteries are severely blocked. During percutaneous angioplasty, a small balloon is threaded through a blood vessel and into the affected artery. Once in place, the balloon is expanded to widen the blocked region, then it is deflated and removed.

Aortic valve surgery – Surgical repair or replacement of the aortic valve might be required if the valve is leaking significantly.

If you or anyone you know is suffering from Takayasu’s arteritis, our expert providers at Specialty Care Clinics will take care of your health and help you recover.

Call 469-545-9983 to book a telehealth appointment for an at-home check-up.